Our venous system

What is it?

The Venous system is a part of our circulatory system.

The circulatory system transports and distributes blood with nutrient supplies and oxygen to organs and tissues, as well as it removes byproducts and waist from them. The circulatory system is composed of a pump - the heart - and distributing and collecting tubes – the blood vessels.

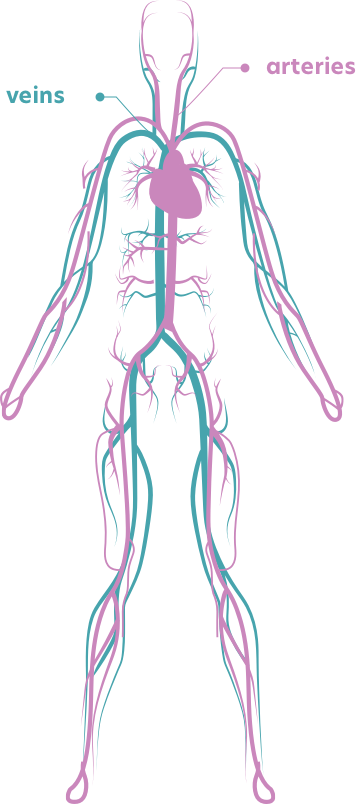

Blood vessels are branching throughout our body and all organs. The vessels distributing from the heart to the periphery are arteries and they make the arterial system, while blood vessels returning blood from the tissues to the heart are veins and they comprise the venous system.

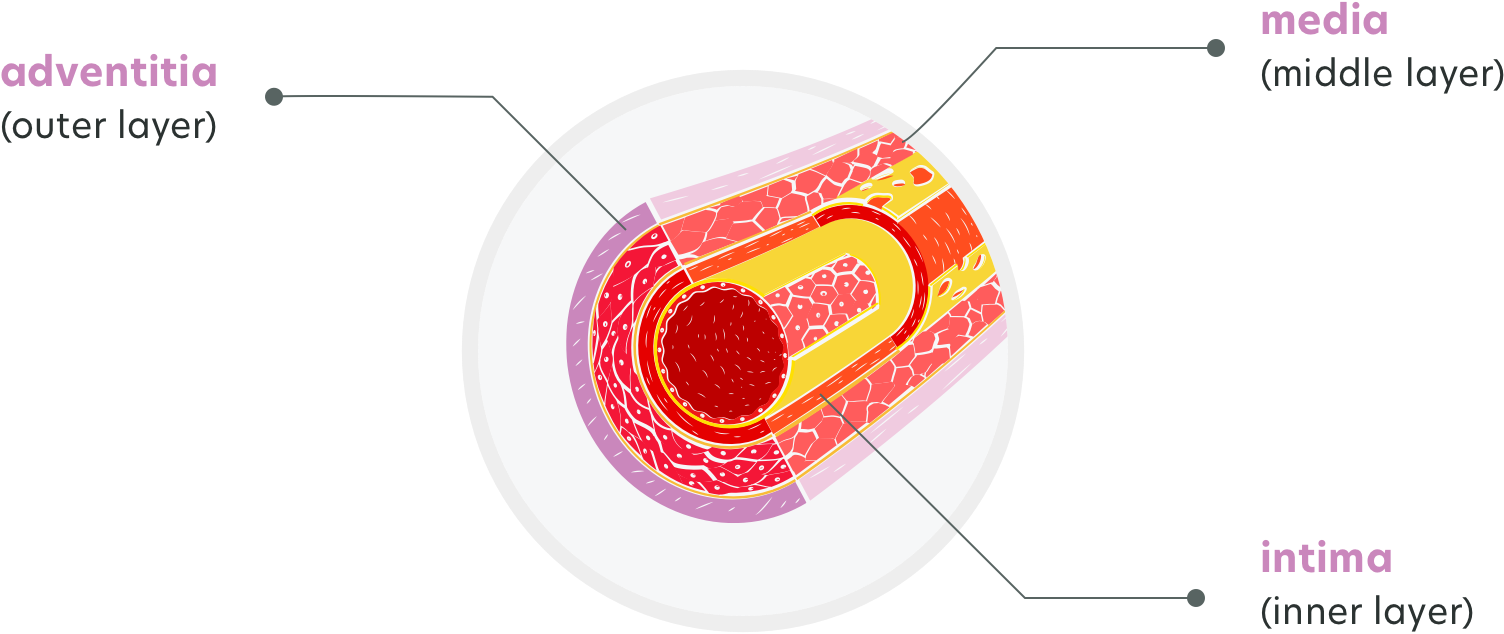

Since blood vessels have to be able to adjust to the needs of our body for blood flow, they contain elastic and muscle fibres in their wall, which in turn consists of three layers:

- elastic fibres help vessels to expand and widen their lumen under pressure, as well as to reduce it back, once the pressure decreases

- muscle fibres enable vessels to contract and narrow the lumen

Veins differ from arteries not just by the direction of the blood flow.

Arteries have more muscle fibers than veins, since they have to be strong in resisting blood pressure (made by heart’s pumping) expanding them too much. On the contrary, veins do not bear high blood pressure and they have less muscle fibers and are able to distend and accept large volumes of blood.

Blood is not pushed through the veins by pumping heart. Therefore, the blood is “pooling” in veins.

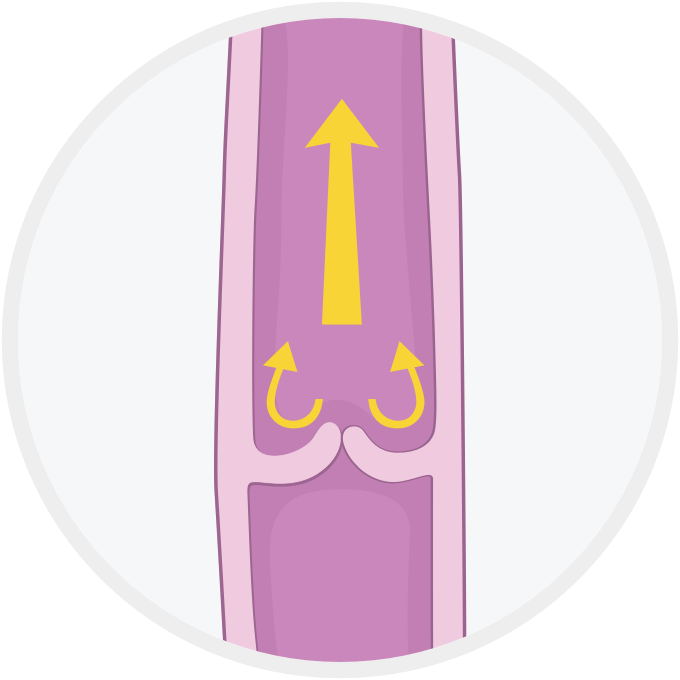

Unlike arteries, veins (mostly in arms and legs) are equipped with valves that protrude into the lumen to prevent the backflow of the blood. These valves allow blood flow only in one way - toward the heart, but prevent blood flowing backwards, from the heart.

How does it work?

A widely branching system of blood vessels transports our blood around our bodies.

Distensibility

A very important feature of the vascular system is that blood vessels are distensible. That allows arteries to accommodate the pulsating blood stream from the heart and provide smooth blood flow throughout the arterial system. Veins are far more distensible than arteries, since their walls are thinner. Even slight increases in venous pressure cause increase in the blood content in venous system, about eight times more than in arteries. By this feature, veins provide a blood reservoir and can store large volumes of blood that can be used whenever additional blood flow is required elsewhere in the circulation.

Importance of the venous system

The venous vessel network is far more branched and complicated than the arterial one.

The venous system transports the deoxygenated blood from the body back to the heart and from there onwards to the lungs. Capillaries and venules, collect the used, deoxygenated blood from all over the body and pass it onto the veins for return transport to the heart.

Due to its build, the venous system has a function of blood storing pool and it contains up to 70% of the blood in the circulation. This reservoir function of veins makes them able to adjust the volume of blood returning to the heart, so that the needs of our body can be matched when changed.

Large veins, particularly those in the arms and legs, have one-way valves. Each valve consists of two flaps (cusps) with meeting edges. As the blood flows toward the heart, it pushes the cusps open like a swinging door. Once the blood has passed through them, these “doors” close by the blood that passed now pushing them backwards with its weight. Therefore, if the gravity pulls the blood back (particularly in legs’ veins) or the blood itself accumulates in a large amount and pushes back, the cusps are pushed closed by the blood, preventing backward flow. Consequently, valves help the return of blood to the heart—by opening when the blood flows toward the heart and closing when blood might flow backward.

Our venous system pumps approximately 7,000 litres of blood flow back to the heart every day.

Anatomy of the venous system

Veins are classified as:

- Deep veins, located deep inside our body, in the muscles and along the bones

- Superficial veins, located in the fatty layer under the skin

- Short veins, called connecting veins, link the superficial and deep veins.

Deep veins have a role to propel blood toward the heart. Their one-way valves prevent blood from flowing backward. These deep veins are laid inside the muscles,

so the surrounding muscles compress them when muscle is active (contracting, moving), thus forcing the blood toward the heart. For example, calf muscle is forcefully compressing the deep veins in the lower leg with every step we make and pushes the blood up the leg and toward the heart.

Superficial veins also have valves, but they are not surrounded by muscles. Subsequently, blood in the superficial veins is not forced by the squeezing action of muscles, and it flows more slowly than blood in the deep veins. Considerable volume of the blood is diverted from superficial veins into the deep veins, through the short veins that connect them.

The ability of veins to function depends on their distensibility, or compliance. Veins in legs are less compliant than those at or above the level of the heart. Veins in the legs are also thicker than those in the brain or in arms. The compliance of veins, decreases with age, and they become less elastic due to reduction in elastic fibres in their walls and an increase in collagen content.

Venous conditions

Veins problems

The most common problems that affect the veins include:

Varicose Veins

A varicose vein is a vein in which blood has pooled, producing distended and swollen superficial vein that looks twisted and may become painful, itching or cause a sensation of tiredness. The most often are in legs and more likely in women than in men.

They may be a consequence of several causes, the most important one being a weak vein wall. This weakness of the wall may be inherited or acquired with age (loss of elastic fibers), obesity or repeated prolonged standing.

When a vein gets distended and elongated the cusps in one-way valves separate and can’t close properly. Under the influence of gravity, a section of the vein below such a deficient valve is subjected to the pressure of a larger volume of the blood. The vein enlarges as it becomes distended and surrounding tissue becomes swollen due to the increased hydrostatic pressure.

Spider veins

Spider veins are enlarged small venous capillaries, mostly in the skin. They can occur as a consequence of varicose veins or can be caused by hormonal factors (particularly in women during pregnancy).

Spider veins cause no pain or other issues. However, being visible on the skin, they might look unappealing.

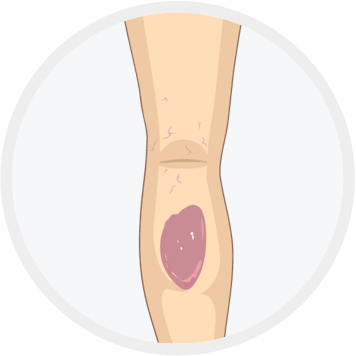

Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI)

Varicose veins and failure of one-way valves can progress to chronic venous insufficiency, especially in obese individuals. Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is impaired venous return (blood flow from periphery toward the heart) causing discomfort, swelling, and skin changes. Extremities can become so inactive that their metabolic demands to be supplied with oxygen and nutrients and released from

wastes are barely met. In this situation, any trauma or pressure can cause cell death and necrosis (venous stasis ulcers).

Thrombosis (Thrombus formation in veins)

A thrombus is a blood clot attached to a blood vessel wall. It can be formed in arteries, but venous thrombi are more common.

Three factors promote venous thrombosis:

- venous stasis (e.g., immobility, age, congestive heart failure),

- damage of veins inner surface (e.g., trauma, intravenous medications), and

- conditions in which blood becomes prone to clotting (hypercoagulable states, e.g., inherited disorders, malignancy, pregnancy, use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy).

Blood clots (thrombi) can occur in the deep veins - deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or in the superficial veins - superficial venous thrombosis.

The superficial veins are usually also inflamed but without clotting (or thrombosis) - superficial thrombophlebitis.

Superficial venous thrombosis is inflammation and clotting in a superficial vein, usually in the arms or legs. The skin over the vein becomes red, swollen, and painful. It is usually treated by elevation, rest and pain killers.

Deep vein thrombosis occurs most often in the legs or pelvis but may also occasionally develop in the arms.

Risk factors

While it’s true that anyone can develop varicose veins, there are certain risk factors that increase chances of presenting them.

Keep in mind that though some risk factors, such as family history and gender, cannot be changed, there are some lifestyle changes to be done to prevent varicose veins from getting worse.

-

Age

The risk of varicose veins increases with age. Aging affects the valves in veins that help regulate blood flow, eventually, causing them to allow some blood to flow back into the veins where it collects instead of flowing up to the heart. -

Sex

Women are more likely to develop the condition, since female hormones tend to relax vein walls. -

Pregnancy

The volume of blood in the female body increases during pregnancy to support the growing fetus, which at the same time leads to enlarged veins in the legs as a side effect. -

Family history

There is a greater chance for a person to develop varicose veins, if other family members had them also. -

Obesity

Being overweight puts added pressure on veins. -

Standing or sitting for long periods of time

Being in the same position for long periods prevents blood from flowing and increases veins’ stress.

Symptoms

While the symptoms of a venous condition can vary widely, some common ones include:

Veins that feel warm to the touch

Burning or itching sensation

Inflammation or swelling

Tenderness or pain

These symptoms are especially common in legs. If you notice any of these and they don’t improve after a few days, you should consult a healthcare professional.

Care

By improving your circulation and muscle tone, the risk of developing varicose veins or getting additional ones may be reduced.

Self-care, such as:

-

Avoiding high heels and tight hosiery

-

Watching your weight

-

Exercising

-

Eating a high-fiber, low-salt diet

-

Elevating your legs

-

Changing your sitting or standing position regularly

-

Wearing compression stockings

-

Food supplements (consult with a healthcare professional prior to taking)

can help you ease the discomfort from varicose veins and may prevent them from getting worse.

If you feel that self-care measures haven't stopped your condition from progressing, see your doctor.

Depending on the stage and severity of the condition, your doctor, in order to alleviate the symptoms and protect the venous system from further deterioration, may propose various methods such as oral therapy, compression treatment and surgery.

Progression of venous conditions

-

No visible or palpable signs

-

Telangiectasias veins

(less than <1mm)

Reticular veins

(1-3 mm in diameter) -

Varicose veins (>3mm)

-

Oedema

-

Secondary skin alterations

(pigmentation, eczema, lipodermatosclerosis, white atrophy) -

Healed ulcer

-

Open ulcer

(often in the ankle area)

1. Katherine A. Lyseng-Williamson and Caroline M. Perry Micronised Purified Flavonoid Fraction. A Review of its Use in Chronic Venous Insufficiency, Venous Ulcers and Haemorrhoids. Drugs 2003; 63 (1): 71-100

2. Diosmin Monograph. Alternative Medicine Review 2004, Volume 9, Number 3

3. Hesperidin. Natural Medicines Database. Professional Monograph. 2/13/2019

4. The British Journal of Surgery: Meta-Analysis of Flavonoids for the Treatment of Haemorrhoids

5. Ramelet AA. Clinical benefits of Daflon 500mg in the most severe stages of chronic venous insufficiency. Angiology 2001;52:S49-S56.

6. Smith PD. Neutrophil activation and mediators of inflammation in chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Res 1999;36:24-36.

7. Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schonbein GW, Takase S. Therapeutic approach to chronic venous insufficiency and its complications: place of Daflon 500 mg. Angiology 2001;52:S43-S47.

8. Le Devehat C, Khodabandehlou T, Vimeux M, Kempf C. Evaluation of haemorheological and microcirculatory disturbances in chronic venous insufficiency: activity of Daflon 500mg. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp 1997;17:27-33.

9. Yoichi Nogata et al. Flavonoid Composition of Fruit Tissues of Citrus Species. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry Vol. 70 (2006) , No. 1 pp.178-192

10. Amílcar Duarte et al. Citrus as a Component of the Mediterranean Diet. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, Vol. IV, Issue 4, (2016) 289-304

11. Jung-Kook Song and Jong-Myon Bae. Citrus Fruit Intake and Breast Cancer Risk: A Quantitative Systematic Review. J Breast Cancer. 2013 Mar; 16(1): 72–76.

12. Carlos A. González, Núria Sala, Theodore Rokkas. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiologic Aspects. Helicobacter ISSN 1523-5378doi: 10.1111/hel.12082

13. Grapefruit and Medication. Total Health. 27 (2): 39. 2005.

14. Carr, Jackie. Five Ways to Prevent Kidney Stones. UC San Diego. April 22, 2010

15. A. Lichota et al. Therapeutic potential of natural compounds in inflammation and chronic venous insufficiency. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 176 (2019) 68-91

16. Bogucka – Kocka et al. Diosmin – Isolation Techniques, Determination in Plant Material and Pharmaceutical Formulations, and Clinical Use. Natural Product Communications Vol. 8 (4) 2013

17. Berne, Robert M, Bruce M. Koeppen, and Bruce A. Stanton. Berne & Levy physiology, Seventh Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier, 2018

18. Hall, John E, and Arthur C. Guyton. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, 13th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2016

19. Overview of the Venous System. MSD Manual Consumer Version. Retrieved June 11th, 2016 (https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/heart-and-blood-vessel-disorders/venous-disorders/overview-of-the-venous-system)

20. Huether, Sue E.McCance, Kathryn L., eds. Understanding Pathophysiology. 6th edition. St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Mosby, 2016

21. Heart and Blood Vessels Disorders. MSD Manual Consumer Version. Retrieved June 11th, 2016 (https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/heart-and-blood-vessel-disorders/venous-disorders/overview-of-the-venous-system)

22. Economos C, Clay WD. Nutritional and health benefits of citrus fruits. Food Nutr Agric. 1999;24:11–18

23. Morand C., Dubray C., Milenkovic D., et al. Hesperidin contributes to the vascular protective effects of orange juice: a randomized crossover study in healthy volunteers. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011;93(1):73–80. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004945

24. Zou Z., Xi W., Hu Y., Nie C., Zhou Z. Antioxidant activity of Citrus fruits. Food Chem. 2016;196:885–896. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.072

25. Testai L., Calderone V. Nutraceutical value of citrus flavanones and their implications in cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2017;9:502. doi: 10.3390/nu9050502

26. Eklöf et al. Revised CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: Consensus statement. JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY Volume 40, Number 6, 2004